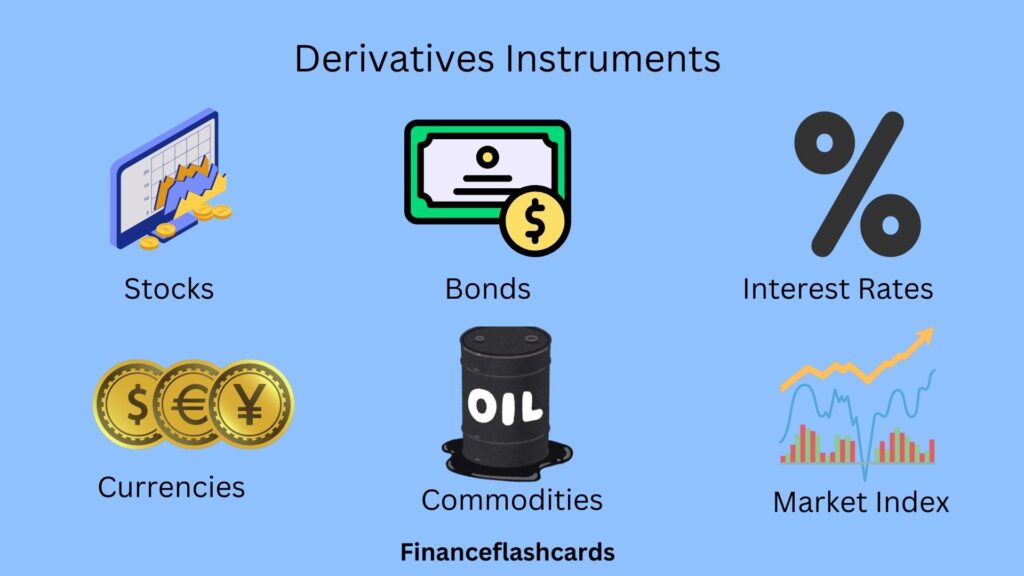

Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset. They are used for various purposes, including speculation, hedging or to shift risk.

Table of Contents

What Is a Derivative?

The term “derivative” refers to a financial contract whose value is determined by on an underlying asset, a group of assets, or a benchmark.

Users of derivatives include hedgers, arbitrageurs, speculators and margin traders. Derivatives are agreements set between two or more parties that can be traded on an exchange or over the counter (OTC).

Derivatives can be used to reduce risk (hedging) or accept risk with the expectation of consistent reward (speculation).

Understanding Derivatives

Types of Derivatives

There are two types of derivative products: locks and options.

Lock products (e.g., futures, forwards, or swaps) link the parties from the start to the agreed-upon terms for the duration of the contract while option products (such as stock options) give the holder the right but not the obligation to buy or sell the underlying asset or security at a specific price on or before the option’s expiration date.

The most common derivatives are futures, forwards, swaps, and options.

Futures

A futures contract is a financial agreement between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a fixed price on a specific future date. It is frequently used to lock in prices and reduce the risk of market fluctuations. Futures contracts are standardized and traded on exchanges.

For example, imagine a farmer growing wheat. The farmer is worried that wheat prices might fall by the time the crop is ready for sale. At the same time, a bread company worries that wheat prices might rise.

This way, the farmer avoids the risk of lower prices, and the bread company avoids the risk of higher costs.

Not all futures contracts are settled at expiration by delivering the underlying asset. Many of the contracts are settled by cash, which is nothing but the difference between the agreement price and the market price.

Forwards

Forwards are just like futures but they are less regulated and mostly trade over the counter, which means they are not regulated and are not bound by specific trading rules and regulations.

Because such contracts are not standardized, they can be tailored to the specific needs of both parties. Given the bespoke nature of forward contracts, they are typically held until expiry and delivered into, rather than unwound.

Options

Options are financial derivative contracts that give the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specific price (referred to as the strike price) during a specific period of time.

American options can be exercised at any time before the expiry of its option period. On the other hand, European options can only be exercised on its expiration date.

Imagine you want to buy a house priced at $200,000, but you’re unsure and want time to decide. You make an agreement with the seller to pay $5,000 for the right to buy the house at the same price within 6 months.

This agreement is like an option. If the house price rises to $220,000, you can still buy it for $200,000, saving $20,000. If the price falls to $180,000, you can choose not to buy and lose only the $5,000. This way, options give you flexibility without obligation.

Swaps

Swaps are another common type of derivative, commonly used to exchange one type of cash flow for another. For example, a trader may use an interest rate swap to convert a variable interest rate loan to a fixed interest rate loan, or vice versa.

As the market’s needs have developed, more types of swaps have appeared, such as credit default swaps, inflation swaps and total return swaps.

Imagine a company in the U.S. has a loan with a fixed interest rate, but it wants to pay a floating interest rate instead. Meanwhile, a European company has a loan with a floating interest rate but prefers a fixed rate for stability.

They enter into an interest rate swap. The U.S. company agrees to pay the European company’s floating interest payments, while the European company pays the U.S. company’s fixed interest payments.

Neither company changes its original loan, but by swapping the payments, they both get the type of interest rate they prefer. This helps them manage financial risks more effectively.

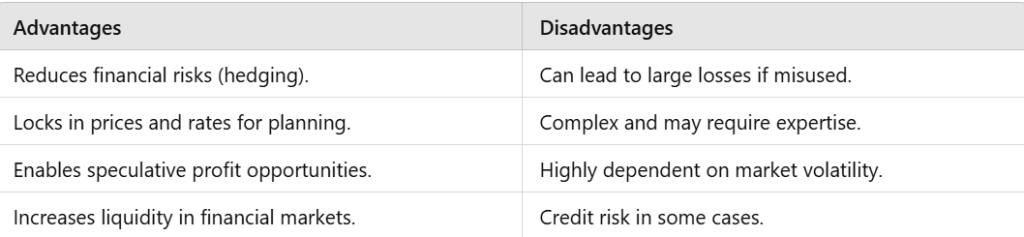

Advantages and Disadvantages of Derivatives

Advantages

Disadvantages