Recent market narratives have increasingly focused on the idea that inflation pressures are easing even as expectations around monetary policy begin to shift. For much of the past year, global markets have operated under a comforting assumption: inflation is largely behind us. Supply chains have normalised, headline inflation has cooled, and investors are confidently pricing in rate cuts from major central banks. But beneath this optimism, a new inflation risk is quietly building, one driven not by wages or commodities, but by artificial intelligence (AI). What was initially celebrated as a productivity revolution may now be creating structural cost pressures, especially through energy demand, infrastructure spending, and technology investment. Increasingly, investors are asking an uncomfortable question: Is AI inflationary rather than deflationary, at least in the medium term?

The Original Deflation Thesis Around AI

The early investment case for artificial intelligence was both straightforward and persuasive. AI was expected to automate routine and repetitive processes, streamline workflows across industries, and materially improve productivity. By reducing reliance on manual labour and enabling firms to scale output with fewer incremental inputs, AI appeared positioned to lower unit costs across the economy.

This expectation was reinforced by history. Previous waves of technological adoption, from the internet to cloud computing and enterprise automation, ultimately exerted deflationary pressure by improving efficiency, lowering marginal costs, and expanding supply.

It was therefore natural for markets to assume that AI would follow a similar trajectory.

That assumption may still prove valid over the long run. However, emerging short to medium term dynamics suggest that the path to those efficiency gains may be more capital-intensive and cost-heavy than initially anticipated.

The Hidden Inflation Channel Behind AI

AI is not just code running on laptops. It is deeply physical and capital-intensive. Building training and running large-scale AI models requires enormous infrastructure. This includes data centers high performance chips, cooling systems, specialised hardware and constant power supply. Each layer introduces cost pressures that are now visible at a macro level.

“The voracious demand for energy and advanced chips from data centre construction is driving up costs … potentially keeping inflation above Federal Reserve targets for longer.”

— Morgan Stanley strategist forecasting that AI infrastructure itself is a material inflationary force.

At a macro level, inflation rises when demand for real resources grows faster than supply. This is precisely what the current AI cycle is doing. Unlike past digital innovations, AI is not only software-driven. It requires physical capital at an unprecedented scale. Training and deploying large language models (LLMs) demands vast data centres, specialised semiconductors, constant electricity, and advanced cooling infrastructure. Each of these inputs competes for scarce real-world resources such as power land, skilled engineers, and capital equipment.

AI runs on data, and data runs on power.

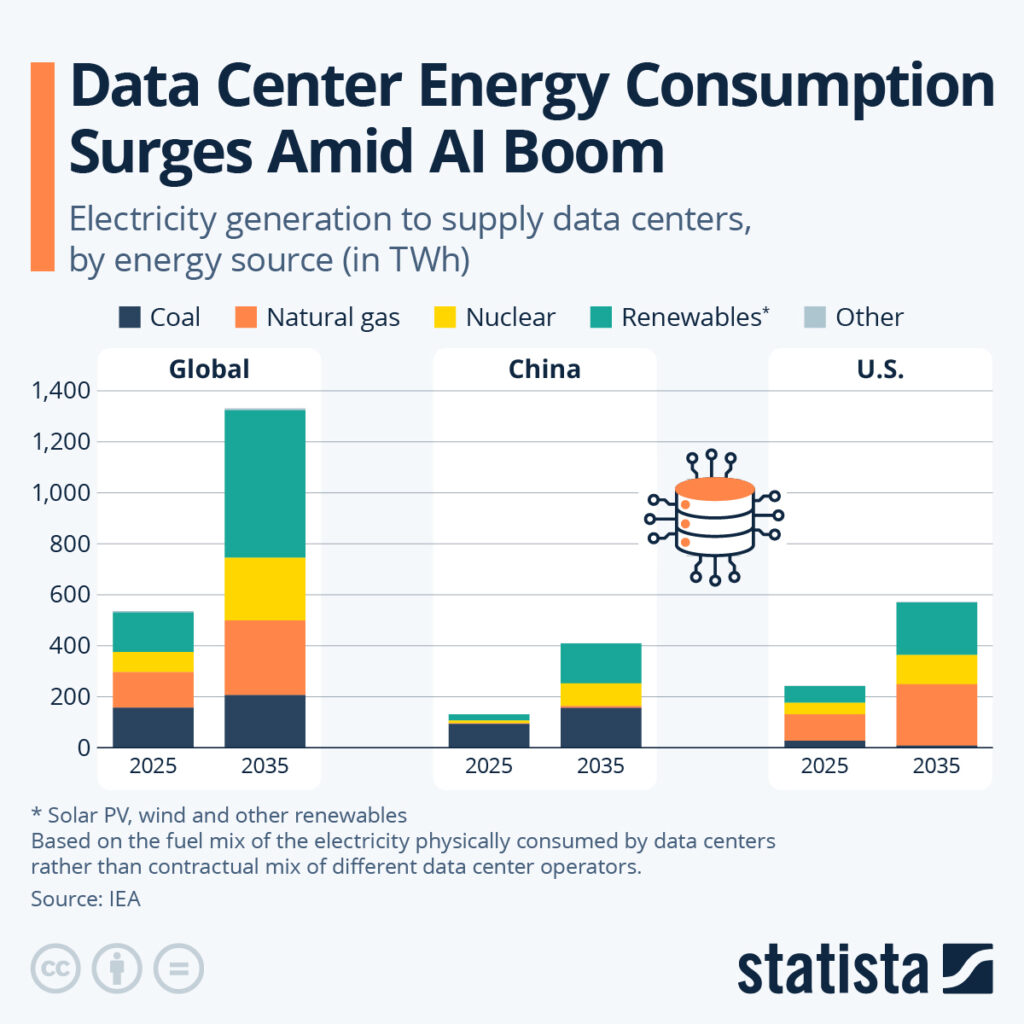

The most visible pressure point is energy. As data centers scale globally, electricity demand is rising rapidly across the U.S, China and worldwide — a trend that helps explain why AI investment may keep inflation stickier than markets expect. In regions such as the United States and Europe energy prices remain structurally higher than pre pandemic levels. AI accelerates demand at a time when grids are already under strain. Hyperscale data centers consume as much electricity as small cities. As AI adoption accelerates utilities are forced to invest heavily in grid expansion, power generation and transmission upgrades. These costs are not absorbed in isolation. They filter through electricity pricing industrial tariffs and public infrastructure spending. For example major technology firms such as Microsoft and Google have committed billions of dollars to expand AI data center capacity, often signing long term power purchase agreements that tighten regional energy supply. This sustained demand places upward pressure on prices even when consumer demand elsewhere is cooling.

Semiconductors form the second channel. Advanced AI chips are complex and capital intensive to produce and concentrated among a small number of suppliers. When companies race to secure computing capacity, prices rise not only for cutting-edge chips but also across the semiconductor value chain. This is not speculative demand. It is an operational necessity. Firms building AI capabilities must spend regardless of the economic cycle which makes the inflationary impulse persistent rather than temporary.

There is also a labour and services dimension. AI infrastructure requires highly specialized engineers, data scientists, and construction expertise. Competition for this talent pushes wages higher at the top end of the skill spectrum. At the same time, professional services related to cloud computing, cybersecurity, and AI integration are repriced upward as demand surges. These costs show up in core inflation, the metric central banks care most about.

Recent deal activity reinforces this dynamic. Instead of slowing investment, companies are accelerating spending through strategic acquisitions and acqui-hires. Large firms are acquiring smaller AI startups not for immediate revenue but to secure scarce talent and proprietary capability. These deals signal that capital expenditure is structural, not cyclical. Even when valuations compress, spending continues. This combination is what makes AI inflationary in the medium term. Demand remains strong while the supply of critical inputs adjusts slowly.

In simple terms, AI is creating a sustained investment boom. Investment booms raise productivity eventually but they also raise prices during the build-out phase. That is the phase markets are in today. Inflation linked to AI is therefore not about consumer excess. It is about capital intensity, resource scarcity and long duration spending cycles. This creates cost-push inflation rather than demand-driven inflation. It is harder for central banks to control because it stems from investment cycles, not overheated consumption. This is why inflation pressures can persist even when headline growth appears moderate and why central banks are increasingly cautious in declaring victory over inflation.

The Cost of Capital Shift Behind the AI Valuation Reset

This is where valuation comes into play.

When interest rates were very low, investors were comfortable paying high prices today for profits that might come many years later. Because money was cheap, future earnings looked more valuable in today’s terms.

AI companies benefited a lot from this because most of their value depends on strong growth far in the future rather than profits right now.

When interest rates started rising, this changed. Higher rates reduce the value of future profits when they are brought back to today. As a result, stock valuations naturally came down even if the companies themselves did not change.

This adjustment is not driven by panic or loss of faith. Markets are not rejecting AI. They are simply being more careful about how much they pay for future growth in a higher-rate environment. It is a shift back to sensible valuation rather than a rejection of the AI story.

Central Banks Are Watching More Than Just Growth

The key risk facing markets today is not a sudden resurgence of runaway inflation. It is something more subtle and potentially more disruptive: inflation that refuses to fall further.

After a period of easing price pressures, investors have grown comfortable with the idea that inflation is behind us and that rate cuts will follow smoothly. But beneath the surface, a new source of persistent pressure is emerging. Large-scale AI-driven investment is sustaining demand for energy infrastructure, data centres, advanced chips, and specialised labour. As a result, price pressures may stabilise above central bank targets rather than continue to decline.

This complicates the policy outlook far more than markets currently acknowledge.

Aviva Investors highlighted this risk clearly in its 2026 outlook. The firm warned that a key market threat could come from central banks ending their rate-cutting cycles earlier than expected or even resuming rate hikes if price pressures build from AI investment alongside renewed government stimulus in Europe and Japan.

This is an important shift. Inflation risk today is no longer primarily about supply chain disruptions, reopening demand or commodity shocks. It is increasingly about structural spending cycles driven by technology transitions and public investment.

What This Means for Rate Cuts

Markets are pricing in easier monetary policy over the coming quarters. Equity valuations, particularly in growth and technology sectors, reflect expectations of falling discount rates.

If AI-related investment keeps core inflation elevated, central banks may find their room to cut rates more limited than investors expect. Even a pause or a slower pace of easing would force a reassessment of asset prices across markets.

This matters most for businesses whose valuations depend heavily on long-dated cash flows. The longer the duration of expected earnings, the more sensitive the valuation is to changes in the discount rate. Small shifts in rate expectations can therefore have outsized effects on share prices.

This explains why AI-related stocks can correct sharply even when earnings forecasts remain intact. The driver in such cases is not company specific weakness but a macro-level repricing of capital costs.

Markets are not questioning the future relevance of AI. They are questioning how much that future is worth today under a higher and more uncertain cost of capital.

A Shift in the Inflation Narrative

The broader macro shift underway is gradual but significant.

Inflation today may be less about temporary shocks and more about investment-led structural pressure. AI represents a long duration capital cycle similar to past transitions, such as electrification, industrial automation or the build-out of telecommunications infrastructure.

History shows that such transitions eventually deliver productivity gains and efficiency improvements. But those benefits tend to arrive after the heavy investment phase. In the early stages, costs rise before efficiencies are realised.

Energy demand increases, infrastructure spending accelerates, and competition for specialised inputs intensifies. These forces can keep inflation elevated even in the absence of strong consumer demand growth.

Markets are beginning to price this reality. The narrative is shifting from inflation being fully defeated to inflation being structurally more resilient.

What Investors Should Watch Going Forward

In this environment, focusing solely on headline inflation numbers is no longer sufficient. Investors should track a broader set of indicators that reflect underlying structural pressures.

- Watch data centre energy demand and electricity pricing trends.

- Monitor capital expenditure plans among major technology firms, which signal the intensity and duration of the AI investment cycle.

- Track core inflation prints in the United States and Europe, where services and input costs remain sticky.

- Pay close attention to central bank language, particularly around neutral rates and structural inflation risks.

- Observe bond market reactions, which often price inflation risk earlier than equities.

- Sustained upward pressure on bond yields may be the earliest signal that markets are reassessing the inflation outlook more seriously.

Key Takeaway

Artificial intelligence remains a powerful long-term growth story. Its potential to reshape productivity industries and business models is very real.

What is changing is the macro environment in which that story is being valued. AI investment is driving sustained capital spending, higher input costs and persistent core inflation pressures. This challenges the belief that inflation is fully behind us and that interest rates can fall quickly without consequences.

Markets are not walking away from AI. They are adjusting valuations to reflect a higher cost of capital and a more complex inflation backdrop.