Agency theory identifies an essential conflict that arises in the corporate world when shareholders (as principals) hire agents (management staff and board members) to manage their business; yet sometimes agents will pursue their own interests (i.e., higher salary or job security or benefits) rather than focusing on maximizing value for their shareholders. According to Investopedia’s definition of the agency problem: “the agency problem exists when agent(s) pursue objectives contrary to those of the principal(s), resulting in conflicts of interest. “According to the statement made by Berle & Means (1932), “…the separation of ownership and management will result in costly consequences due to lack of close monitoring by large numbers of shareholders over the activities of the managers.” Jensen and Meckling (1976) will further define what is meant by the cost of an agency occur in relation to the following three components:

- Monitoring costs (e.g., audits, board oversight)

- Bonding costs (e.g., insurance or bonding performed by any manager)

- Residual losses (i.e., losses that are incurred by agents which arise from their suboptimal decisions)

As noted, agency conflicts can be expensive in real life. Habib and Ljungqvist (2005) determined that, on average, U.S. firms are $1.432 billion below their highest-performing competitors because of inefficiencies associated with agency conflicts such as poorer investment levels, slower growth rates, and loss of economic benefits, among others caused by managers acting against the interests of shareholders.

The internal mechanisms used by companies to reduce these costs include: utilizing boards of directors (particularly independent outsiders) to monitor the actions of managers, creating and implementing audit committees, and providing incentives to executives within compensation tied directly to the stock price through equity compensation. Indeed, the percentage of CEOs that have equity compensation (generally in the form of stock options) increased from 30% in 1980 to 70% in 1994.

Managers can also get discipline from the market when there is a market for corporate control (takeovers and activist shareholders), allowing for the replacement of underperforming managers (John & Senbet, 1998) However, John and Senbet will also explain that sometimes internal mechanisms and external mechanisms will supplement one another. For example, if there is a strong market for takeovers, it will often balance out weaknesses in the board. Regulation has also had an influence on corporate governance as regulatory enactments after major scandals (e.g., Sarbanes-Oxley) created consequences for fraud and increased the audibility of auditors in order to maintain honesty of agents.

Essentially the purpose of governance is to align managers and shareholders’ interests. According to one study, internal governance and external governance mechanisms have a common goal to align manager’s utility and shareholder’s utility. In table heavy research the commonality of independent boards leads to a quicker dismissal of bad CEOs and more board support for actions benefitting shareholders (e.g., poison pill votes). Now, due to the experience indicating outside board members can assist in alleviating agency issues, regulators (e.g., pension funds and stock exchanges) are prescribing the importance of board independence.

Costs and Evidence

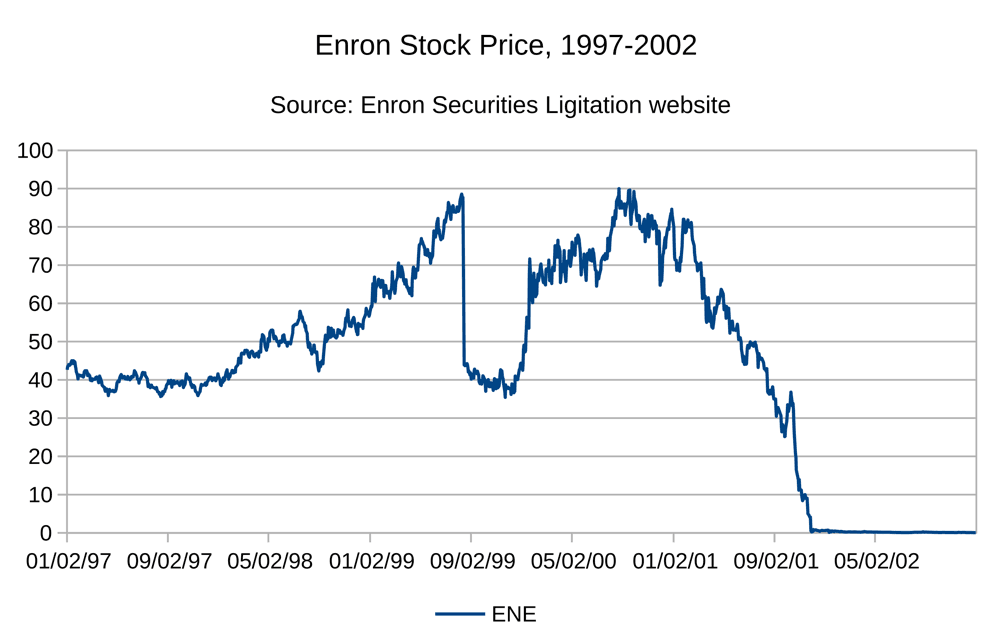

Agency conflicts have the potential to erode value when the actions of management can be detached from those of other shareholders. Management may conceal bad performance or incur too much risk on behalf of short-term interests (based on the way it affects their stock options), to the detriment of the long-term performance of the company. In addition, management may also take personal advantage of their position (known as “perquisites”) which can dilute the returns to other stakeholders, such as shareholders. There are numerous examples of how agency conflicts have created issues for shareholders in the past. In 2001, Enron created fictional profits and hid real losses in its accounting, which allowed the company’s stock to remain high (around $90), but once the truth about the company’s performance finally came out, Enron’s stock fell to under $1. Overall, shareholders lost billions of dollars as a result of management’s actions, with the result being only a small fraction of the total amount lost being recovered through a shareholder class action lawsuit against Enron (only $7.2 billion of $40 billion). Typically, agency costs are reflected in lower firm value, higher cost of capital, or lower growth. If management owns only a small percentage of a company’s stock, they will avoid riskier (but profitable) projects (known as under-investment) and pursue projects that result in no additional value to the company (known as over-investment).

Direct fraud: the worst instances of this type of fraud include Enron and WorldCom where managers manufactured false books or created fraudulent activities that personally benefited them, and at the same time created a completely distorted image to shareholders on how well their companies were performing. Statistical evidence shows there is a beginning correlation between good governance and alignment of pay, and increases in the value of a company, but this correlation varies widely depending on which study you are reviewing. The example provided to illustrate this connection is the one provided by Hall and Liebman (1998); they demonstrated (through their research) that the grant of equity had dramatically increased (approximately $155k in 1980 and approximately $1.2M by 1994), and that these equity grants were meant to reduce agency costs, and firms with better governance tend to have lower cost of capital.

Analysts agree that monitoring is important. One review stated that if the majority of the Board is made up of outside directors then it is likely to take actions that are in the best interest of the shareholders, i.e., they will terminate the employment of underperforming individuals, they will approve the acquisition of companies that are fair from the perspective of outside directors. In contrast, weak boards are often indicative of accounting inaccuracies and scandals. Since the events at Enron and other similar companies, there have been numerous attempts to revise or develop legislative measures that provide oversight of boards and their auditing processes (e.g., audit committees must consist of directors that are independent of the Board, auditors will be subject to mandatory rotation, CEO’s and CFO’s will certify their respective company’s results and performance).

As one commentator stated, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (2002) is the “mirror image” of Enron; the failures that Enron was perceived to experience exist in the terms of provisions of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act.

Case Study : Enron Corporation (Houston, 2001)

Enron had been the ‘darling’ of the investing community on Wall Street. The price of its stock increased by over 311% during the entire decade of the 1990s. By December 31, 2000, Enron’s market capitalization had exceeded $60 billion. Agency conflicts caused by top executives Kenneth Lay, Jeffrey Skilling, CFO Andrew Fastow, etc., entered into elaborate and complicated off-balance sheet transactions nearly every month in order to hide the losses they were incurring and inflate the earnings of the company. They were able to do this with the usage of special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) and aggressive mark-to-market accounting practices that made the reported earnings of the company appear far greater than what it actually was. This resulted in large bonuses and stock options being paid to managers even if the operational fundamentals of the business were incurring serious losses and generating negative cash flow.

Although Enron was perceived to have an independent, well-functioning board of directors, and professionally managed, many analysts argue that the board members failed to adhere to their regulations and duly exercised their oversight duties. During the scandalous conduct of the company, Fastow and other company executives manipulated and misled the board and the audit committee(s) regarding the actual risk and debt positions of the company. As an example, Fastow concealed the $30 million he earned personally from the SPVs operated by the company before he resigned.

The value of Enron’s common stock went down to nearly nothing after the scheme failed. Example: In 2000, Enron’s stock was valued at close to $90 (see figure), however, by late October and early November 2001, it had fallen below $1. On December 2, 2001, Enron filed for bankruptcy, it was the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history at that point. The fallout from this was tremendous; many shareholders and employees lost “billions in pensions and stock prices,” and only recovered a small portion through litigation. Many executives were indicted (CEO Skilling went to jail; Lay passed away prior to his sentencing) and the auditing firm for Enron, Arthur Andersen, ceased to exist.

There were sweeping reforms that were prompted by Enron’s failure. Congressional hearings from December 2001 until July 2002 led to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) that significantly increased oversight of corporations. SOX made destroying records and “attempting to defraud shareholders” into significant criminal offenses and required independent audit committees and CEO/CFO certification on the accuracy of financial reports. Essentially, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act contained solutions for the agency issues that were revealed due to Enron’s failure. As one government report stated: “The provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley mirror the deficiencies in Enron’s structure on a point-for-point basis.”

Conclusion

Every large corporation has an Agency Problem – the conflict between shareholders (the principal) and executives (the agent). The agency problem can appear as a benign form (what happens when an executive simply does not perform) and a catastrophic form (what happens to a company like Enron that commits fraud and collapses). Through understanding the moral hazard of Agency cost and gaining knowledge about similar cases such as Enron, businesses and regulators will be able to develop effective corporate governance that: (1) creates meaningful independent boards of directors; (2) aligns executive compensation to the interests of the shareholders; and (3) places legal limitations on executive actions – thereby helping manage the actions of executives so that they correspond to the interests of the shareholders and minimizing the costs to the shareholders associated with the Agency Problem.

Bibliography

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74.

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783.

- Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2003). The fall of Enron. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 3–26.

- Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. (1932). The Modern Corporation and private property. Harcourt, Brace & World.