Game theory is one of the most powerful intellectual tools ever created to understand strategic decision-making. Originally developed by mathematician John von Neumann and economist Oskar Morgenstern in the 1940s, and later revolutionized by John Nash, game theory offers a framework to analyze human behavior whenever multiple decision-makers interact, each with their own incentives and information.

Today, game theory applies to:

- Capital markets

- Corporate strategy

- International relations and war

- Public policy

- Cryptocurrencies and decentralized systems

- Business negotiations

- Poker and professional gambling

- Dating, marriage, and friendships

- Everyday decisions such as “who texts first?” or “should I apologize?”

As with other influential theories—like behavioral economics, probability, or evolutionary biology—game theory is both rigorously academic and intuitively human. It helps explain why we behave the way we behave.

This article is a deep, yet accessible, walk through Game Theory and its applications, with storytelling, examples, formulas, and even humor to keep things engaging.

1. Game Theory 101: Foundations and Key Concepts

1.1 Strategic Form Games

A strategic-form (or normal-form) game consists of:

- Players

- Strategies (actions available to each player)

- Payoffs (rewards/penalties depending on the chosen strategies)

Formally represented as:

G = {Ρ, S(i), u(i)}

Where:

- Ρ = set of players

- S(i) = set of strategies for player

- u(i) = payoff function mapping strategies to numerical outcomes

1.2 Nash Equilibrium

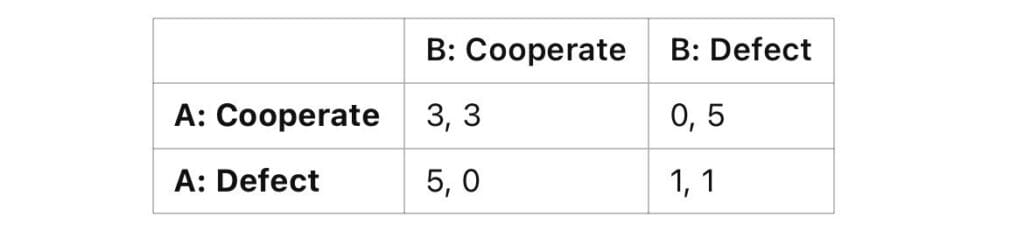

1.3 Payoff Matrices and Best Responses

2. Game Theory in Finance and Capital Markets

2.1 Trading as a Strategic Move

2.2 Market Signaling and “Games of Incomplete Information”

3. Game Theory in Poker: The Art of Strategy Under Uncertainty

3.1 Poker as a Bayesian Game

3.2 Nash Equilibrium and GTO (Game Theory Optimal Play)

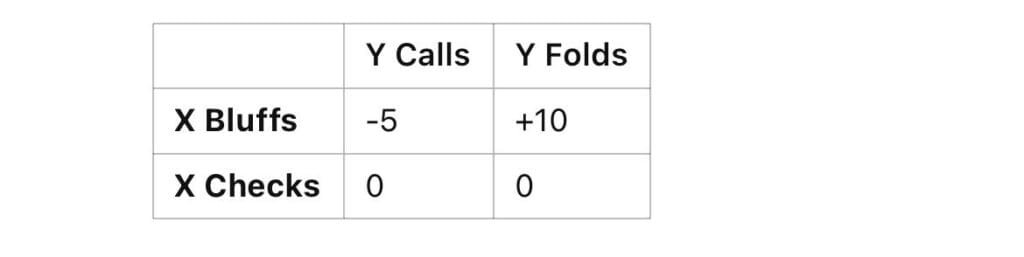

3.3 Simple Bluffing Matrix

3.4 Expected Value (EV)

EV = Σ (Probability of outcome × Value of outcome)

This is another important concept that not only poker players understand; it’s also well known among jewelers and sneaker traders, who often use it to negotiate and bargain prices. EV is always present—even when they flip a coin to settle a buying or selling price. Some might argue this is gambling, but hustlers know that with enough volume and over the long run, whether you call it gambling or not, every trade carries risk. There are countless factors outside our control, and movement is king.

Example:

Buyer and seller disagree between $13,000 and $16,000 for a ring.

They flip a coin.

If the jeweler bought it for less (say $10,000):

If he loses (sells for $13k): profit = $3k

If he wins (sells for $16k): profit = $6k

Expected value (EV) of a fair coin flip:

EV=3k+6k/2

EV=4.5k

So on average, if he repeats this many times, the upsides cover the downsides.

This is standard expected-value math.

3.5 Poker as a Microcosm of Life

4. Game Theory in International Conflict: The Cold War

4.1 Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)

4.2 The Cuban Missile Crisis

5. Game Theory in Relationships and Dating

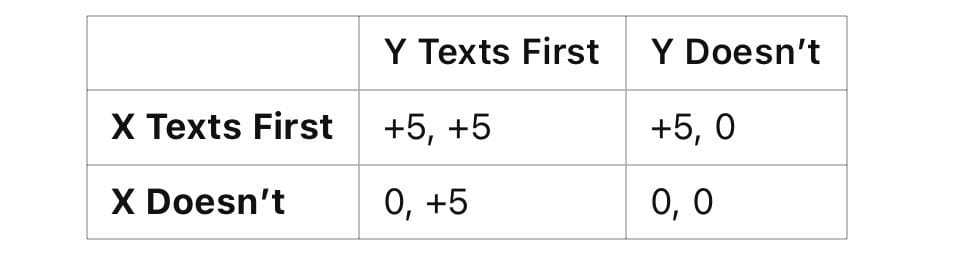

5.1 The “Who Texts First?” Game

5.2 The Apology Game

Game theory teaches a slightly uncomfortable lesson:

The world is not driven by emotions first — it is driven by strategic expectations of

other people’s behavior.

Markets crash not because we panic.

Wars don’t happen because leaders are “evil”.

The world is a network of strategic interactions, and game theory reveals the hidden logic behind them.